Pensacola’s Early Days

On August 15, 1559, Don Tristan de Luna and 1500 people in 11 ships arrived at the charming Pensacola Bay to settle and make the area their home. Included in the population was the Alcalde Ordinario, the local law enforcer and judge.

The new settlement didn’t last long. On September 19, 1559, a hurricane struck the small community. The residents struggled for two years to survive as a settlement but without success. Those who remained boarded a ship back to New Spain (Mexico). It wasn’t until 1698 that another European settlement was attempted. In 1722, the Spaniards settled on Santa Rosa Island, just east of the site of present-day Fort Pickens. However, when a hurricane suddenly appeared on the horizon, the residents fled to the mainland, near present-day Seville Square.

The British Arrive

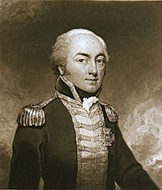

In 1763, British troops arrived and took possession of Pensacola. Two months later, the West Florida Commission appointed George Johnstone as Captain-General and Governor-in-Chief of West Florida. On November 27, 1764, members of the British Royal Council appointed themselves and 19 other residents as Justices of the Peace for British West Florida. They appointed John Johnstone as Marshal.

Crime and Punishment

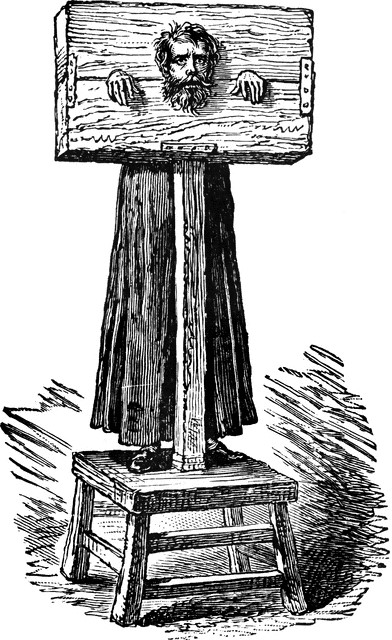

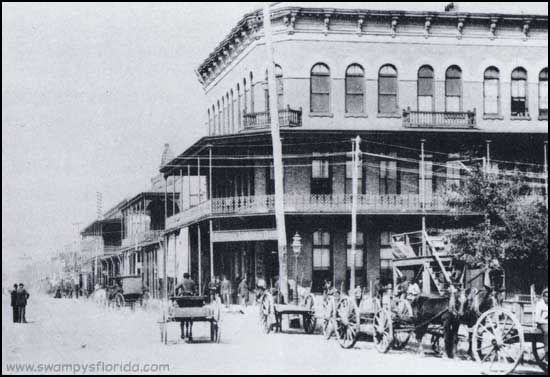

When the British controlled Pensacola, it was a small community with houses mostly near the Bayfront. Shipping was the most important industry, bringing in business from across the world. With the maritime profession came sailors, which created a rowdy waterfront lifestyle. Law & order was important to the citizens of Pensacola. Punishment took on many forms. Besides jail, many creative forms of punishment were used to punish, correct, and deter. Prisoners were often sentenced to be shackled to a pillory in the middle of the town square — today’s Ferdinand Plaza. On February 7, 1769, Pensacola council minutes reflect the decision to pay Marshal Johnstone thirty dollars to erect a pillory.5 Incidentally, neither rain, heat, cold, nor an appeals court had any effect on a judge’s sentence. It was the custom that citizens would jeer and throw slimy garbage and rotten eggs at prisoners who were sentenced to endure the pillory. Flogging was also a common punishment. Known as “The Whipping Act of 1530” in England, it was adopted by the British courts in Pensacola. The punishment was carried out when the marshal would tie the prisoner to a vertical pole in the ground by his wrists and beat him. Tarring & feathering was also popular. The prisoner would be stripped naked, have hot tar poured or smeared over his body, and feathers thrown on top, so they stuck to the tar — for humiliation. The prisoner was then usually paraded around the town for all to see. This form of punishment often caused permanent injury to the defendant, and occasionally death. One story describes a prisoner who was tarred and feathered, then set on fire and paraded up Palafox Street. William Dunbar, a Pensacola citizen, related the story of one young woman accused of murdering another one; she was convicted and sentenced to have her hand cut off and then to be hanged.

An American Town

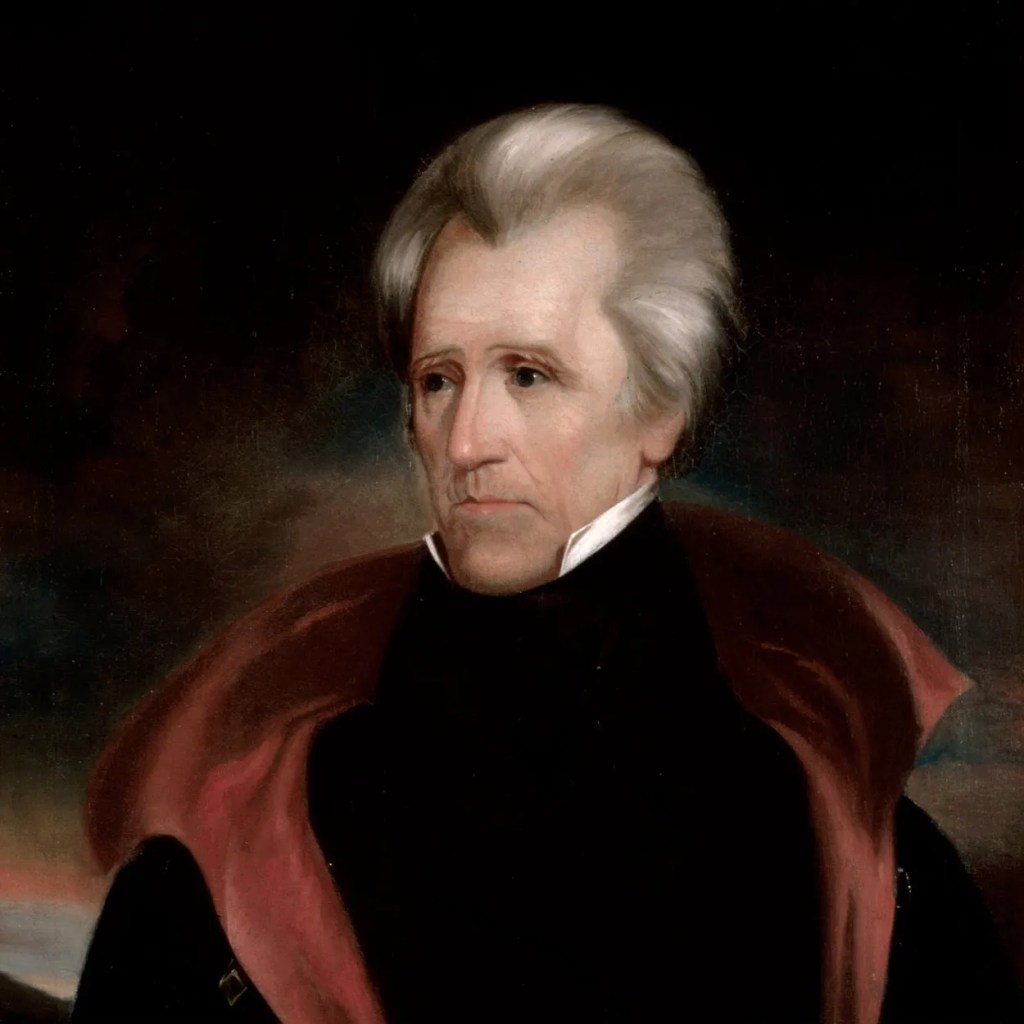

Two words describe Pensacola in July: hot and humid. Combine that with the other conditions in 1821 — insects, sandy streets, no air conditioning or electric fans and no modern hygiene practices — and it would be difficult to call Pensacola “delightful.” The same year, Colonel Don José María Callava was the final Spanish governor of West Florida. Callava had risen through the ranks of the Spanish military rapidly, mostly due to his outstanding war record. He was appointed governor in 1819, before his 40th birthday. As such, he enjoyed supreme power in West Florida. Andrew Jackson had been chosen by the President to accept West Florida for the United States – in Pensacola. Both Jackson and Callava had some common traits. They both were powerful. Both were war heroes. Both were egotistical. And both were widely popular within their circles. The two men agreed that Florida would become part of the United States on July 17, 1821 at 10 AM.

On the appointed day, General Jackson rode into town and immediately joined his wife for breakfast. Sharply at 10 AM, amid much ceremony and many American and Spanish soldiers and civilians, the Spanish flag, which had been flying for almost 60 years, was lowered while the Spanish national anthem, La Marcha Real, played in Ferdinand Plaza. The plaza was named after Ferdinand VII, the king of Spain. Then, the flag of the United States was proudly raised while the Star-Spangled Banner sounded. The ceremony ended with Jackson accepting the territories and the Spanish soldiers boarding their ships and departing. For the first time, the flag of the United States was raised over the territory.17 Over the next two days, Jackson made appointments to set up the local government. One of the appointments was for James Craig to act as Alguacil (the Spanish word for constable.)

Florida Becomes a State

On March 3, 1845, as his last act as President, John Tyler signed the act into law that gave statehood to Florida. The newly acquired status as a state, the navy yard, and the growing fishing industry caused an increase in the population, as well as the joie de vivre of the town. Pensacola was growing, and the town officials knew it was going to take more than one or two men to keep order. Further, the town was quickly becoming a major port, bringing in sailors and visitors from all over the world. Funds were allocated for the hiring of several additional police officers. During this time police officers’ mode of travel was by foot. An officer walked to work, to his assigned area, walked while on duty, walked to the stationhouse after his shift, and walked home. It made for tough cops. Pensacola was growing, and so were the police.

The Civil War Years

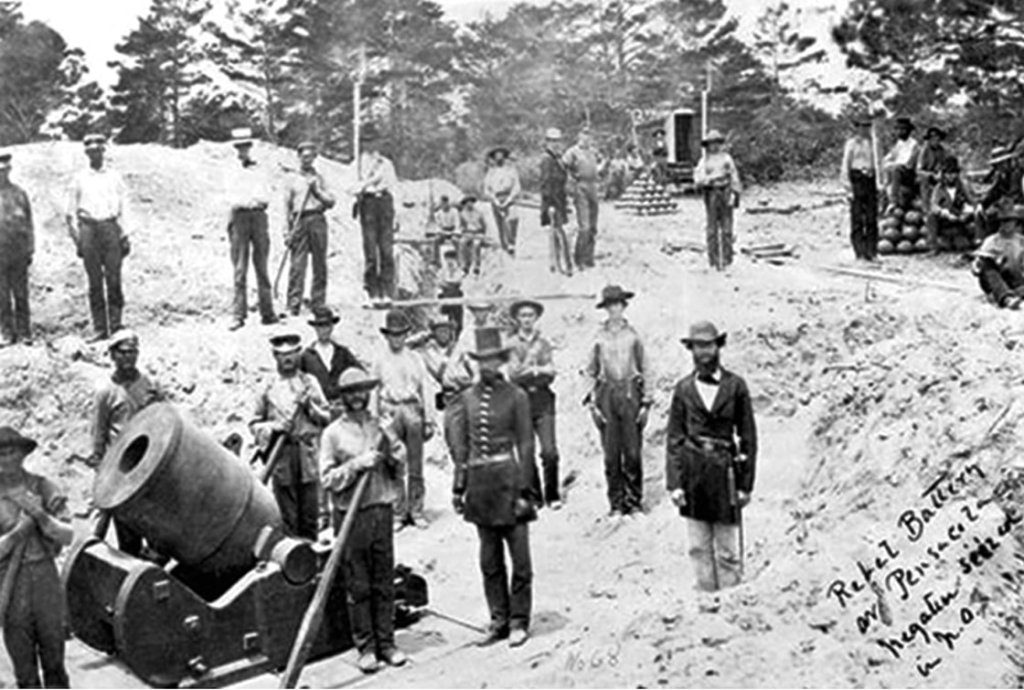

The atmosphere in 1860 Pensacola could be described as anxious uncertainty. Or perhaps it was certain — certain war. The impending war between the states was on the minds of everyone. It seemed clear that the only solution to the problem of North vs South was the direction the nation was heading — to fight it out. The arrival of the war brought with it both anxiety and excitement.

On January 10, 1861, Florida seceded from the union. On March 11, 1861, General Braxton Bragg arrived in Pensacola and assumed command of the Confederate troops there. On March 19, eight thousand Confederate soldiers left Pensacola for Tennessee, leaving a skeleton crew to defend the town and nearby installations.

On April 12, our nation officially entered into civil war when Fort Sumter was fired upon. One week later, on April 19, Bragg declared martial law in Pensacola. This meant, in short, that the laws of Pensacola were enforced by members of the Confederate military, not the Pensacola Police. There are no records indicating what services — if any, the civilian police provided, but there is usually action taken to assist the military in such cases.

On May 7, Confederate Colonel Thomas Jones was in charge of the troops in Pensacola. When word came that the formidable Union Admiral David Farragut’s fleet was anchored off Mobile Bay, Colonel Jones removed confederate supplies and artillery from Pensacola. On May 9, they set fire to much of the town and left. On the same day, most of the Pensacola citizens abandoned the town, which was surrendered to the Union Forces. City business was conducted from Greenville, Alabama. Less than 100 citizens remained in the vacant town. There is no record of a law enforcement presence in the town during the War. The following day — May 10 — Union Lt. Richard Jackson and his troops moved into and occupied Pensacola. They were warmly greeted by acting mayor John Brosnaham. Northern troops occupied the town and were allowed, unchecked, to roam the town. This left the town in a dilapidated state, with some homes in ashes. Pensacola, initially occupied by Union troops, was eventually completely abandoned.

In 1865, Confederate forces surrendered, ending our nation’s worst conflict. Federal troops occupied the Florida capitol city of Tallahassee on May 10. Ten days later, the American flag was again raised over the State Capitol. In Pensacola, citizens began to trickle back into town and try to rebuild the town as well as their lives. However, the military presence remained, which administered most of the law and order in the town until the local government could resume control. On June 25, 1868, the State of Florida and the City of Pensacola were readmitted into the union. The job of rebuilding a nation began.

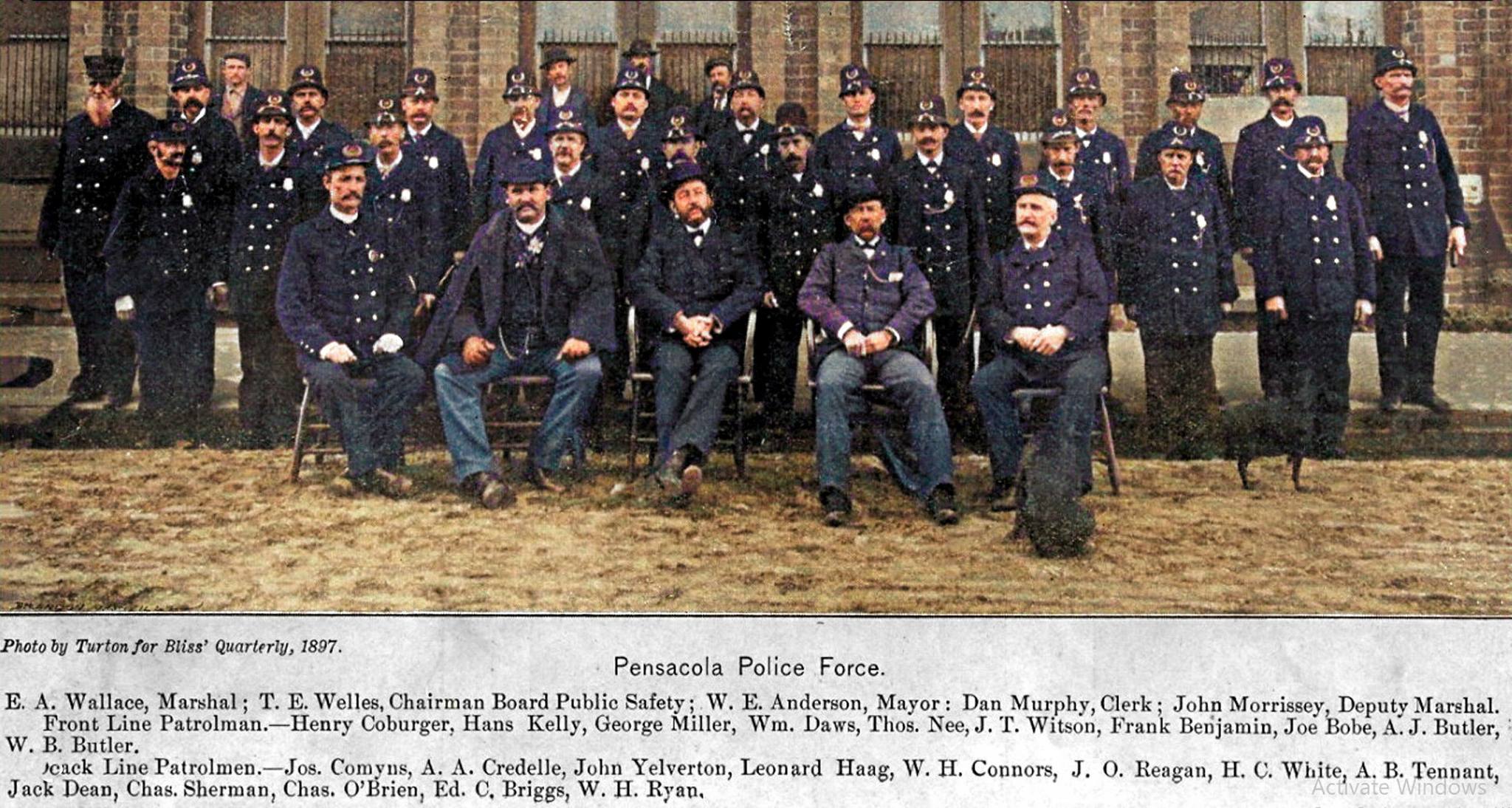

Uniformed: Pensacola-style

On February 17, 1884, the Pensacola Police Officers donned their first uniforms. “…Pensacola looks more than ever like the city she is. Keep her going!” was the cry from the local newspaper. The uniform, purchased at the officer’s expense, consisted of a long navy blue wool coat with two rows of brass buttons and a brass police badge, navy blue wool pants, black leather boots, a black leather belt with a brass buckle, a navy blue police custodian helmet with a hat badge encircled by laurel leaves, and a truncheon (club) which usually hung on the non-club hand side of his belt. If an officer carried a firearm, he had to use his own, but most did.

The new Smith & Wesson Triple Lock .44 revolver was popular, but many officers preferred single-action revolvers, or even the repeating pistols used during the Civil War. In addition, most officers sported a large, heavy duster or handlebar mustache. Suddenly, the citizens of Pensacola began to view their officers in a different light. The police became the pride of the city!

Reorganization

After the Civil War, the government in Pensacola was ruled by Republicans. Democratic Governor Edward A. Perry, a Pensacolian, urged the Florida legislature to revoke the city charter of Pensacola, which was dissolved on February 16, 1885, and replaced by a provisional government. As a result, the Pensacola Police Department, previously under the command of

Marshal Duncan Mallett, was reorganized two days later. Joseph Wilkins, who served as the Escambia County Sheriff (the county where Pensacola is located), was appointed the new City Marshal and Chief of Police.

For the first time, by state constitution, the structure of the police department was spelled. Sixteen officers, under the command of Marshal Wilkins, were now able to keep the city safe more effectively. This new arrangement caused several problems. Because the governor’s dissolution of the old form of government and the creation of the new one — controlled by the state, an underlying feeling of resentment by the locals began to grow. But the immediate problem was the appointment of the county’s sheriff as marshal. Even though the city commissioners wanted to guide the marshal’s movements and directions, he stood as an appointed official — by the governor, not by them. This problem came to a head in the closing weeks of 1886 when Joseph Wilkins was asked — forcefully — to offer his resignation as marshal. He resigned as marshal under protest, but not as sheriff. He then filed a lawsuit to have the case reviewed by the courts. He maintained that the office of Chief of Police should be ruled null and void, because it could not legally usurp the authority of the elected office of Marshal.

From 1821 to 1885, law enforcement in Pensacola grew from a one constable to a force of 16 police officers. Now, officers would be on duty all day every day. The first officers were John B. Griffin, Ed Cope, J. G. Gonzalez, Felo Roche, James Farinas, M. C. Gonzalez, John Adams, Mike O’Neal,

Monthly pay was:

Marshal Wilkins — $100 (a two-room house cost $300)

Deputy Marshall Griffin — $80 (a 3-year-old steer cost $62)

Captain Touart — $70 (a horse-drawn buggy cost $75)

Officers — $60 (a breech-loading shotgun cost $60)

When the new department was organized, Marshal Wilkins set new rules:

Officers could not sit down while on duty.

Officers could not drink “spirituous liquor” in the police station.

Officers had to be able to read and write in English, never have been indicted and convicted of a crime, of physical health and vigor, of good moral character, and of unquestionable energy.

The more intelligent officers were stationed on the main streets.

An officer could not use his club or pistol except when he was protecting his life or if someone showed resistance.

An officer could not leave his beat unless he was taking an arrestee to the police station or for an emergency.

Officers could not visit bar rooms while on or off-duty.

A n officer could not be absent for roll call more than three times a month.

Tidbits

On April 20, 1885, City Commissioner W.D. Chipley believed that prisoners should be treated better, so he ordered that the ones who worked be allowed three meals a day instead of two, as was the previous norm.

The Department issued each officer one piece of equipment that was effective in the heat, cold, rain, even snow if needed — a whistle.

During the month of December 1885, seventeen prisoners escaped. Fifteen of these were working outside under the guard of one officer, and two of them left from the police station.

Interesting…

On June 17, 1895, the city commission approved new rules for prisoners:

Prisoners after arrest and while in the station house using profane, insulting, or indecent language will immediately be confined to the dungeon and given only bread and water.

If a person was fined for an offense but could not pay the fine, he was ordered to work for punishment instead. If he refused to work, he was also placed in the dungeon and fed only bread and water.

The board of public safety was also busy with officer discipline. They handled several suspensions and dismissal hearings every month. In other words, about 20% of the police department changed monthly. Some examples were:

On July 24, 1895, Officer W. H. Ryan came before the Board of Public Safety on the charge of discharging a firearm unnecessarily in the city limits. Ryan pled guilty but stated that he would do it again if he had to. He stated that he shot an escaped prisoner who had been convicted of arson and attempted murder. The case was dismissed.

On October 21, 1895, Officer C. Habberman was dismissed from the Police force for (1) Inefficiency of duty (2) Living with a known prostitute without being married and (3) Obtaining money from a woman and refusing to return it. The officer was dismissed.

In 1896 the Board approved changes in the jail. At the time, female prisoners and male prisoners were housed separately, but under the same roof, and they could still talk to each other. Marshal Wallace ordered a new jail built next door and the female prisoners, described as “irreputable,” were housed in the new building.

On April 1, 1896, Marshal Wallace complained to the Board of Public Safety that new, louder whistles were needed, because the current ones could not be heard half a block away. He won his argument and the department received a new, louder whistle for every officer.

On December 1, 1896, Mayor Anderson stated that prisoners who had been allowed to leave the jail at different times, had been found drunk on the streets and had to then be brought back to the station to sober up. This was occurring when the prisoners should have been working. In response, the Board of Public Safety ordered that the following notice be posted in the marshal’s office: “No officer shall permit any prisoner to leave or be absent from the prison without a permit from the mayor or the marshal.”

If a citizen had an issue with an officer in 1896, he or she would file a complaint with the Board of Public Safety. On December 11, 1896, Mr. John Lear made a complaint against Officer E. C. Briggs for “unwarranted clubbing” him during his arrest. The board of Public Safety investigated the incident and found that the clubbing was justified, and Officer Briggs was found not guilty.

A New Century

With the coming of the 1900s, Pensacola began to expand and required more police officers. The city commission allocated more funds to hire additional officers. During the next several years, about a dozen new positions were created. As a result, Chief Wilde assigned more officers to the downtown area and some in the newly established neighborhoods such as North Hill and East Hill. During the next 18 years, the police department’s budget nearly doubled.

Officers were expected to conduct themselves in a manner befitting their office. The Department began testing officers periodically in their knowledge of the laws and the locations of businesses and streets in their areas. They were also required to be in excellent physical shape to perform their duties. Officers began to work in teams of two, and partners were required to walk the streets for better protection. A local ordinance stated that if two officers were walking down a busy sidewalk and shouted, “Gang Way,” people had to move out of their way. Respect or Fear? — probably both.

An advantage offered to officers around the turn of the century was the collection of rewards for capturing wanted persons. For instance, on June 24, 1900, Officer Ward, with the assistance of a citizen, Isau Vau, captured a convicted murderer from Alabama. The sheriff of Lowndes County, Alabama, sent an $8 reward for the deed and it was split between the two.

Oh, by the way…

On June 26, 1901, the City of Pensacola authorized the first plain-clothes officer if it did not cost the city any money. Surveillance and investigations could now by carried out with more efficiency.

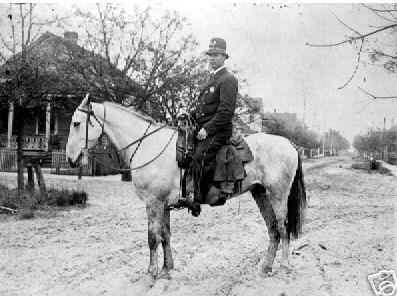

In 1895, automobiles became available, and were mass-produced beginning in 1905. However, the police department continued using buggies, horses, and walking. On September 5, 1900, a report was made to the Board of Public Safety that one patrol horse was out of commission due to an injury — it had been kicked by another patrol horse.

Pensacola Police Communications

The city bell. Everyone had heard it, and everyone knew what its function was. A large, 3000 lb. bell at the police station was rung on special occasions, for celebrations, and when needed to communicate, such as a fire or other emergency. Officers were required to know the following:

One ring from the tower means that the Captain of the Watch is wanted. Two rings the mounted officer is wanted. It is his duty to go to the nearest telephone and call up the station; if no phone is handy, he must go to the station at once and report.

Three rings mean that all the officers ON and OFF duty MUST report at the police headquarters AT ONCE. (NO EXCUSE WILL BE TAKEN FROM ANY OFFICER FOR FAILING TO REPORT TO THIS CALL.)

It was a welcomed change when, on May 17, 1909, telephones were first installed in the police station followed by call boxes positioned at street corners around the city. From these call boxes, officers could call the police station, maintaining and coordinating their activities. It became department policy for officers to call in periodically and check for calls on their beat. However, if there was an emergency, the desk sergeant still rang the city bell, but the rules changed. For instance, if the officer was working Beat 3, the desk sergeant would ring the bell three times indicating him to call the station. The boxes remained in place until the early 1980s. For an officer to make a call on a police box he was given the following directions:

“Open the outside and inside door of the box. Strike six blows with your finger on the gutla percha in the lower corner of the box. Then push in the gutla percha pin in the upper corner of the box, count to fifty (50) and then pull the lever.”

Oddly enough, officers found this new method of communication to be effective. The boxes were located strategically around the city so that there was always one close by if needed.

Less than a month later, a new police call box was used to report one of the department’s own. On June 10, 1909, Officer Joseph G. Hilliard, who was off duty, visited The Alligator, a bar located at Wright and Tarragona streets for a drink. While there, his pistol dropped from his pocket onto the ground. Seeing his intoxicated condition, the employees asked him to leave, and they later filed a complaint at the police house. Meanwhile, Hilliard proceeded to another bar at the corner of Tarragona and Garden streets and began cursing and acting disorderly toward a man named Joe Morris. The police were called, and Officer W. M. Malone was dispatched to the bar using the new call boxes. When Officer Malone arrived, he refused to arrest a fellow officer. The behavior of both officers brought them reprimands.

Even though the radio, known as a “wireless,” had been around for some time, new developments occurred in 1913. Woodrow Wilson gave the first presidential press conference via radio on March 14, 1913. Over the next several years, the worth of the new technology of radio was realized. The use of radio for naval vessels, music, news, and long- distance communication came into play across the world. Soon, police departments began to experiment with the use of one-way radios for dispatching patrol cars and for the dissemination of information. Finally, the technology came to Pensacola. On Thursday, April 23, 1925, the Pensacola Journal reported the following: “Council instructed city manager Roark to advertise for bids for purchase of a police radio short wave set. Council was told that the Radio Corporation of America has already offered to the city a radio set for $2320, and which would require only $200 a year to operate.” After delays and budget constraints, the system was finally installed in all patrol cars. The base system was installed in the desk sergeant’s office at the police station.

For the previous 60 years, the city bell had been used to dispatch. However, after the installation of the radio system, the bell had to be taken out of use. According to the January 2, 1936 edition of the Pensacola News Journal, “It was the only time since the construction of the jail building that the desk sergeant and turn-key on watch at the time have not swung the bell rope lustily by way of celebrating the new year.” The first transmissions of the radio system from the station to the patrol cars occurred on January 4, 1936. The content is not known. The Pensacola Police Department dispatcher was born!

Unfortunately, the radios in the cars could not transmit — only receive. The desk sergeant put out calls to a patrol car three times in the hope that the officer heard at least one. It didn’t take long for the radio system to be put to the test. A few hours after the radio was tested, a call was put out to Officer Clinton Green, dispatching him to respond to the Piggly Wiggly on Palafox Street to apprehend two shoplifters. Three minutes later they were in custody. Pensacola was proud of her new purchase.

When the location of police headquarters changed in 1956, a sufficient dispatch section was not provided for. The desk sergeant had doubled as a dispatcher. Now, however, a room was set aside for dispatchers. Officers had two-way radios where they could communicate with dispatchers, but not with each other. But the two-person dispatch room was only 6’x 6’. Dispatchers from that era tell the story that, to get in or out of the room, one was required to climb over the other. Later, dispatchers moved to a much larger room — 8’x 12’. Today, it is difficult to over-emphasize the importance of the Police Communications Center. It is the very nerve center of the entire department. Officers speak to telecommunicators more often than any other employees. It is vital to the police function in Pensacola.

The Police Profession becomes more…Professional

One problem that the world of law enforcement suffered from was a lack of training. Chief Caldwell realized the occupation of police officer was no longer simply a job. More and more often it was viewed as a profession. Therefore, it was necessary to initiate formal training for officers. In an interview with Chief Caldwell, he stated that he helped design a new school in which students were required to attend and graduate from to become a police officer. Consequently, the beginnings of the Florida police academy were established. Later, Chief Davis was key in the expansion of the police academy to become an established institution in the police profession throughout the state. Today, every law enforcement officer in Florida is required to complete state-regulated training, pass a state exam, a polygraph, and a psychological exam before being certified as an officer.

The average Pensacola police officer encounters enough bizarre and life-threatening events to write a riveting action novel. The high-speed chases, burglaries, household disputes, death investigations — the police have seen it all. For many centuries, the little corner of the world, along the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico has seen many inhabitants. As the population increased, crime escalated as well, creating the necessity for an effective law enforcement. The Pensacola Police Department has served its citizen through the city’s rich history. Pensacola’s finest carry on the tradition of excellence through protecting those around them, creating a legacy for others to follow.

Sgt. Mike Simmons (Ret.)