Suicide or Murder?

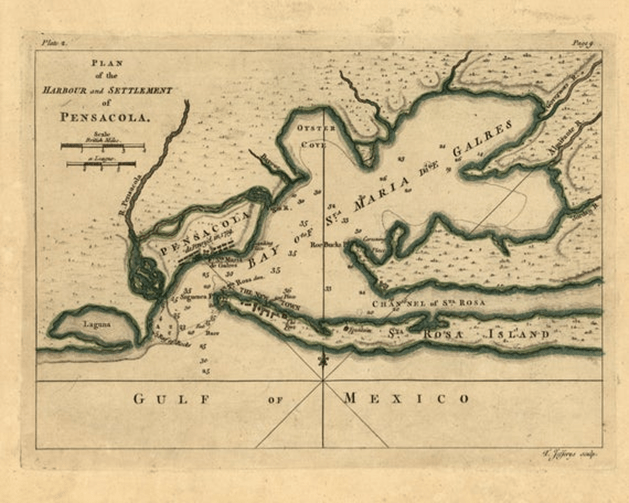

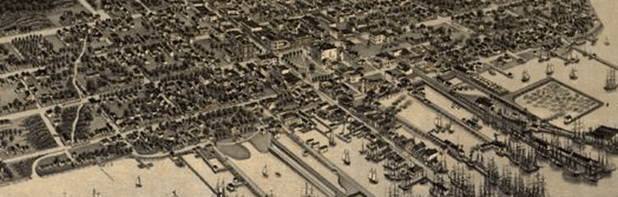

He is known as Pensacola’s leading citizen. Through the tumultuous years of British rule in Pensacola, Elias Durnford was the glue that held the town together. And… maybe he was lucky to have lived through those years. Elias Durnford was born on June 13, 1739 in Ringwood, UK. As the intelligent young man he was, he decided to pursue a commission in the British Army as a civil engineer. After spending several years in the military – mostly aboard ships – Durnford’s talents were realized when he was assigned to the new frontier town of Pensacola. He accepted the assignment with enthusiasm and, upon his arrival in 1764, he immediately began laying out a grid for a proper British town. It was then that he met his two leaders, Governor George Johnstone and Lt. Governor Monforte Browne.

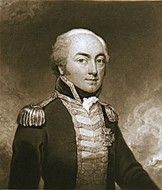

George Johnstone was Scottish born in Dumfriesshire in 1730. A proven brilliant leader in battle, Johnstone was outspoken and often found himself at odds with his superiors. Although he commanded men and ships during battle, he was not well-liked. He was involved in several duels and was even accused of bribery. When he was promoted to Governor of West Florida in 1764, his naval career had already spanned 19 years. While governor in West Florida, he openly kept a concubine by the name of Martha Ford, with whom he sired four children. Because of his failure to play well with others, it was a surprise to no one that he and his lieutenant, Montfort Browne, didn’t get along.

Montfort Browne was Irish, from Cornwall. He served with the 35th Regiment of Foot during the seven year’s war (1756-1763). His career was tarnished when he faced a court of inquiry which found against him in 1763. He found solace through an appointment as Lieutenant Governor of British West Florida. Upon his arrival in the capitol village of Pensacola, he began to have difficulties with Governor Johnstone, his immediate superior. Besides his increasingly strained relationship with his boss, he was investigated by British officials for unscrupulous bookkeeping irregularities.

As far as anyone knows, Johnstone and Browne never got along with each other – ever. Browne even filed complaints on Johnstone to the British Crown. Finally, in 1767, the British Crown recalled Johnstone home to answer those complaints. This, of course, left Monfort Browne as acting Governor of West Florida. Further, it caused Browne to consider that he might be appointed governor permanently, which may have been his motivation all along for filing the complaints.

John Eliot was born on June 2, 1742 in Port Eliot, St Germans, Cornwall of an influential family. At the young age of 10, he was already a midshipman, and a 3rd Lieutenant at age 15. In this position, he worked on the Augusta for George Johnstone. Soon, Her Majesty’s Navy retained Eliot as Captain. He commanded several ships from 1759-1766. During this time, he and his crew were taken captive by French privateers. His family paid for his freedom, but he was praised by his crew and superiors for his heroic actions during their captivity. On March 16, 1767, John Eliot was recommended for the position of the new governor of the frontier settlement of West Florida. After the Earl of Shelburne considering his choices, he appointed Eliot, effective immediately.

In the two years since Browne had gotten rid of rival Johnstone, he no doubt thought about ways to obtain the title of governor. On Sunday, April 2, 1769, while Browne was nearby in Mobile, Alabama, Governor Eliot arrived. With the help of Elias Durnford, Eliot settled in and began to set up his office. A few days later, Browne returned home to find that he was no longer acting governor. His dreams of occupying the office of governor were suddenly crushed. Further, Browne learned that an investigation into his behavior toward Johnstone was underway by Eliot. “Because of this young man – this junior officer, I will not be governor and will probably be stripped of my position as lieutenant governor.” Browne said to himself. “What can be done?” But…maybe something.

The first order of business after Governor Eliot arrived was to conduct the investigation on Browne. On Monday, May 1, Eliot brought the older man into his office for an interrogation. No record exists of the interview, but it was most assuredly not pleasant – no doubt heated. Eliot made accusations toward Browne about his conduct. Meanwhile, the entire community held its collective breath. The encounter between the top ranked officials in their town was taking place, and it was not pleasant. The record shows that the two men had dinner at Eliot’s quarters, then Eliot interrogated Browne well into the night. John Eliot was never seen alive again.

Eliot could not be located the next morning, so a search was organized. The 27-year old governor was found in his office, dead. He had been lynched. Browne, now self-appointed acting governor, proclaimed Eliot’s death a suicide. Browne said that he had been with Eliot “dining and spending time with him” and was surprised that he would end his life.12 Despite any evidence or the townspeople’s suspicions, Browne was never charged.

Monfort Browne was renamed temporary governor. However, the complaints kept coming into England regarding Browne from the colonists in Pensacola. Browne sent his newly appointed lieutenant governor, Elias Durnford, to England to answer the charges.

While he was in England, Durnford met a young lady named Rebecca Walker. After a short romance, the two were married on August 25, 1769. Rebecca accompanied Elias to their new home in West Florida. Besides a new wife, Durnford returned with more news – his own appointment as governor.

Monforte Browne was finally ousted from his position and from Pensacola. While preparing to leave, Browne became involved in a dispute with a local trader and challenged him to a duel. The duel took place and Browne prevailed but did not kill his opponent. He was detained in Pensacola until his victim’s survival was obvious. On August 29, 1778, Browne participated in the famous siege of Rhode Island. Afterwards, accusations of cowardice and incompetence were leveled against him. Consequently, he was removed from office permanently. He died two years later. Governor George Johnstone retired, and lived a quiet life. He died of throat cancer on May 24, 1787. Elias Durnford and his wife, Rebecca decided to make Pensacola their permanent home. When Governor Peter Chester arrived, he calmed matters. Durnford was still a trusted confidant, serving as governor until the arrival of Chester on August 10, 1770. Afterwards, he and Rebecca enjoyed their nine children. Durnford served on the West Florida Council until 1778. He died on June 11, 1794 in Trinidad.

First Prisoner of Distinction

In August 1821 – Just over a month after Pensacola became an American town, the city jail housed its first celebrity. Actually, the jail wasn’t even really a jail. It was described as the previous soldiers’ quarters with a guard stationed outside. As soon as the new government was established, disputes over land grants surfaced. Some of the new “Americans” laid claim to the tracts that had previously been owned by wealthy Spaniards. In one of the disputes, a woman came before Judge Brackenridge with a complaint that the land willed to them had been taken by the local traders Panton, Leslie and Co. She took the case to the Spanish court who found for her but would not enforce the ruling. The answers to this claim and many of the others lay in the papers that were in the possession of Domingo Sousa, lieutenant of the former Spanish governor, Colonel Jose Callava. Both men were still in town. When Judge Brackenridge and his American officials demanded the papers, the lieutenant claimed he didn’t have the authority to release them. He then took the papers to the home of Callava for safekeeping. Governor Andrew Jackson, who was not fond of Callava, inserted himself into the matter. He sent a contingent to the home of Callava, demanding that he release the papers. Callava tauntingly refused, claiming both illness and diplomatic immunity. He also said the he couldn’t understand the English demand, nor the translators that came with them. Finally, he claimed that he knew nothing about the papers in question. Brackenridge and his men searched through the papers and found the ones associated with the complainant, but Callava would not release them. This made Governor Jackson furious. He summoned Callava to his office. A “colorful” dispute took place between the current and former governor (accounts differed) and ended with Jackson ordering the arrest of the Spaniard and some of his men18. Jackson also dispatched officials to Callava’s home to confiscate the papers. A jovial Colonel Callava and his men were taken to the abandoned soldiers’ barracks and jailed there. The quarters were old, dirty, not sufficient, and beneath the colonel, according to one of his men. The guards reported overhearing the prisoners laughing at Jackson’s manner and mocking him. As they occupied the large cell, chairs, tables, candles, food, and wine were brought in by the Spaniards who had remained in Pensacola. In other words, the prisoners enjoyed the sentence they received. They were released the following day.

After a long stay from April to October in Pensacola, the Jacksons were eager to get home. Rachel left Pensacola on October 1, 1821 for her home in Nashville. General Jackson followed a few weeks later. His resignation letter as governor of the territories of East and West Florida soon followed.

Pensacola’s Escape Artist

In 1827, the Old Spanish Trail had been around for a long time…since the Spanish were in West Florida in 1559! It was the only road from Pensacola to St. Augustine. Everyone who made the trip took that route – traders, settlers, politicians, and messengers. Colonel Andrew Jackson even took it. It was later lengthened west to New Orleans, and then much later, when automobiles came on the scene, to California.

Thomas Jones was an official mail carrier for West Florida. He regularly made the trip from Alaqua (Walton County) to Pensacola and back again with bags full of mail. The well-worn trail was fraught with many dangers and obstacles, including deadly harassment from Native Americans, rivers & streams that had to be crossed, and wild animal attacks. Needless to say, the two-day trip was precarious, even for a veteran traveler such as Jones.

On July 14, 1827, while Jones was on the trail, he was approached by two men, one of whom had a gun and the other a knife. The man with the gun shot at Jones, missing his head by less than an inch, and the other stabbed at him, but only ripped his clothes. Jones managed to escape, flee to the nearest town, and report the incident.

A manhunt ensued. Identifying one of the attackers was an easy task for the officials, especially since Martin Hutto had committed such crimes many times in the past. He was apprehended, arrested and transported to the only jail in West Florida – the one in Pensacola.

The old jail wasn’t much. In fact, it was badly in need of repair. Vincent Pintado, a local mapmaker, had created a Pensacola map in 1813 which showed a “Public Prison.”

“How hard would it be to break out of here?” Hutto must have asked himself. “I don’t know, but I might try it.”

This jail, located at Alcaniz and Intendencia Streets, was recorded in a local newspaper in 1827 as being in deplorable condition. Therefore, it was no surprise when it was discovered that Hutto had escaped. On September 5, 1827, a reward of $80 was offered for his apprehension. He was suspected of fleeing to Butler County, Alabama.

In November, Hutto voluntarily turned himself in, anticipating an acquittal when the judge came into town later that month and held court. Unfortunately, Judge Brackenridge did not come for his usual November hearings, so Hutto had to wait until May of 1828. Fearing that Hutto would escape again, he was held in the military jail at the US Army camp known as Cantonment Clinch, located on the shore of Bayou Chico.

Hutto escaped from the Army jail on Jan. 23, 1828. A reward of $30 was offered this time. Hutto was quickly recaptured and stood trial on May 7, 1828. He was convicted by the jury and held in the Pensacola jail while awaiting sentence. On May 15, Hutto again escaped. A fifty-dollar reward was offered this time. Hutto was recaptured and returned to Pensacola in October 1828 where Judge Brackenridge sentenced Hutto to two years in prison.

On March 27, 1829, Hutto escaped for the fourth and last time – this time also from the Pensacola jail, never to be heard from again. The city fathers finally realized that they needed to address the problem of the old jail.

The Branded Hand

In 1844, Pensacola was a southern town which was deep in the middle of the slavery issue of the day. Like most southern towns, some slaves lived in Pensacola, but not as many as a lot of places in the South. Because Pensacola was different from most southern towns – mostly due to the presence of the military – pro-slavery sentiments abounded. A few of the wealthy landowners owned many slaves, upward near 60. Most of those who did have slaves owned only 1 or 2. The vast majority of the city’s residents did not own any slaves. Many were vehemently opposed to the idea of one human being owning another.

Jonathan Walker was a white man who lived in Pensacola and opposed slavery. Walker, originally from Massachusetts, was a devout Christian who did not believe that one person should own another one, despite that it happened in Biblical times.

On June 22, 1844, Walker boarded a boat occupied by several black men. The destination was Nassau, The Bahamas, where the men would find freedom – thanks to Walker. Even though slaves regularly came and went throughout Pensacola, the discovery of the slaves’ disappearance caused fingers to be pointed at law enforcement. The June 29 edition of the Pensacola Gazette issued a scathing editorial criticizing the Pensacola police for not catching the slaves before they boarded the boat.

Of course, sailing in the warm waters of the Gulf in July caused many of the men to be ill, making for a long and turbulent journey. Further, on July 8, the boat was stopped and boarded by the captain and crew of the schooner Eliza Catharine. Believing that Walker was stealing slaves, the captain escorted the boat to Key West, where he appeared before a magistrate. He was ordered to be returned to Pensacola to stand trial. He arrived in Pensacola on July 19, met by Deputy U. S. Marshal James Gonzales, who Walker said treated him humanely.

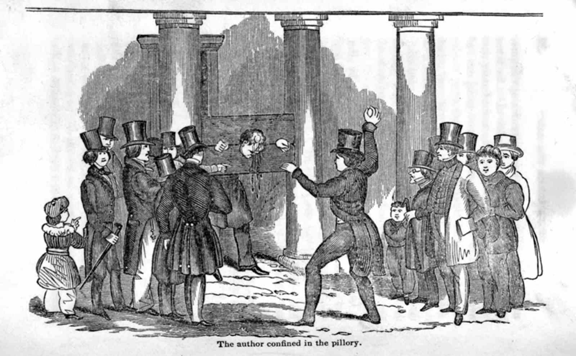

Stealing property, or escorting people to their freedom – which was it? Walker was convinced that the courts would have no choice but to see that a person’s freedom is more important than another person’s property. He was wrong. After half an hour, the jury came back with a verdict of guilty. The sentence was unusual in today’s terms. Walker received from the judge fifteen days imprisonment, be locked in the pillory (wooden stock) and exposed to rotten eggs and garbage for an hour and have “SS” for Slave Stealer branded into the palm of his right hand. He was also ordered to pay a $150 fine.

The accepted practice for the hour in the pillory was to cover the head of the accused. As Walker’s head was being covered, the owner of two of the men who escaped – George Willis – pulled off the cover and threw rotten eggs at him. After his hour, he washed up and was taken to the courtroom. His hand was tied to a post and U. S. Marshal Ebenezer Dorr sizzled the brand onto his palm for 20 seconds, while a silent Walker remained still. The prisoner was then sentenced to be incarcerated for 15 days. The trial made national news. The case of Jonathan Walker occurred during a time when it was assumed that the majority of northerners were against slavery, while it appeared that most southerners were pro-slavery, Once again, Pensacola was not typical. Protests against the arrest and sentence of Walker soon took place throughout the town. The basis of the protests was that slaves are people and should not be bought and sold as property and that Walker’s efforts to assist another person to freedom was more important than a person losing property.

A book entitled The Branded Hand; The Trial and Imprisonment of Jonathan Walker was written by the prisoner and enjoyed immense popularity nationwide, as did a poem entitled The Man with the Branded Hand – written by John Greenleaf. These brought national attention to Walker, to the case, and to Pensacola.

Jonathan Walker, a man of great discipline, had a habit that benefits us today. He kept a daily journal of his experiences and being in the Pensacola prison was no different. An interesting entry is the description of the jail: “The jail is a brick building of two stories, about eighteen by thirty-six feet, having upon each floor two rooms, the lower part for the occupation of the prisoners, and the upper part for the jailer’s family. The rooms for the prisoners are fifteen to sixteen feet square, with double doors, and two small grated windows from six to eight feet from the lower floor. Overhead is a single board floor, which but little obstructs the noise of the upper part from being distinctly heard below, and vice versa.”

On February 5, 1846 (1½ years after his trial and sentence), Walker was still in prison! A friend smuggled a pickaxe into him. Using it, he escaped, but was caught. His fine was paid, and he left Pensacola, never to return.

Duels

The history of men having differences and settling them is as old as history itself. The tradition of the honorable manner has certainly changed over the years. In today’s culture, if one man offends or insults another, fists will fly…or worse. Not long ago, the words “Let’s take it outside!” were heard. In medieval Europe, the honored tradition of dueling became popular. This continued into the new world, especially among members of the military. In the Old South, when one gentleman besmirched another – especially regarding his wife – the offended party was expected to show great indignation, saying something like “Ah dumand satisfaction, Suh!” Interpreted, this meant an apology, explanation, or proof of the offense was expected to be provided. The satisfaction could be immediate, or it could come within a day or two, giving the offender time to gather his evidence, give his apology – written or verbal – or explain his remark. However, if the offending party was unable offer proof, and could not or would not explain or apologize, it was part of “The Code” of a gentleman to challenge the offender to a duel. If the challenge was not accepted, the challenged offender would be considered a coward, and the practice of “posting” – posting a declaration in several public places that the man was a coward – took place.

If he accepted the challenge, written accounts of the incident were requested from each participant and witness who were present at the time of the offense. This was required so that it would be clear that there was an intentional affront, that the insult was meant to be – an insult. If the challenge and acceptance stood, a time and place would be agreed on. This administrative work was carried out by each duelist’s second. A second was a friend or colleague chosen by each man to communicate, clarify and, if possible mediate. If the duel occurred, the second stood aside to shoot the opponent if he cheated. The challenged person chose the type of weapon – pistols, long guns, swords, knives, daggers, axes or clubs could be used. Sometimes, a pair of dueling pistols or swords was provided, and these could amount to quite a sum – according to the status of the participants. Most of the time, though, each man used his own weapon. Pistols were the most common.

Often, according to the popularity of the duelists, a crowd would gather to watch. Occasionally, the challenge became quite the social event. If possible, a surgeon was on hand to patch up one or both parties. The parties stood an agreed distance apart, and the seconds would, one last time, ensure that this was the last resort. If so, the duel would begin. With bladed weapons, the duel proceeded much like what we know as a knife fight, with both parties circling and trying to find an opportunity to cut the other. However, if firearms were used in the duel, both parties had to stand still and take the shot of the other while shooting. The challenged shot first. Hit or miss, the challenger shot next, if he was able. To feint, duck or run-for-cover was considered cowardly. Usually, if conflict went this far, both parties would be shot – maybe killed. Often one party would be shot and the other killed. The “winner” was often arrested and, if the “loser” died, the winner was charged with murder. Bad outcomes on both ends.

During the 1800s, local laws were passed in many communities outlawing the long tradition of dueling, although the laws did little to curb the practice. Popular opinion ruled. Dueling in Florida became illegal on December 28, 1824 – it was considered murder. If a duel was said to be scheduled, the local police showed up and stopped it, arresting one or both parties if necessary. Often, the police were not aware of the scheduled incident, arrived too late, or chose to turn a blind eye to the matter if they felt it should proceed. However, when the War between the States was over, many people reconsidered the value of human life, and the popularity of duels declined.

In Pensacola, a location was set aside for duels. A beautiful spot on the southeastern corner of town is known as Dueling Oaks. The place – covered in gorgeous live oaks – overlooks Pensacola Bay, near the more modern 17th Avenue Trestle. As was stated many times, it is truly a beautiful spot to die. Most of the challenges were not as formal as described above. Often, the challenged talked it out, exchanged money, or fought it out. However, if a duel was scheduled, everyone knew where it would be, including the police. There are instances of duels being fought in other locations, however. Palafox Street is one example.

There exists an account of a young lieutenant in General Andrew Jackson’s regiment who was challenged to a duel and was killed. Jackson reportedly was very fond of the young man. This was another reason that Jackson was keen to leave Pensacola.

Stephen Mallory, a man from Key West, met a young lady named Angela Moreno, of the wealthy Moreno family of Pensacola. After they wed, the couple raised a family (9 children) in Monroe County, Florida. Stephen held several government offices, including United States senator from Florida. When the Civil War broke out, he was appointed Secretary of the Navy of the Confederacy by President Jefferson Davis. At the end of the war, Mallory spent a year in prison for treason. After his release, he returned to live with his family in Pensacola, unable to hold office. Returning to practice law in Pensacola, he ironically became an outspoken proponent for the education of African-Americans, who were now free.

This caused problems between Mallory and the local newspapers. William Kirk, a local editor, was very critical of Mallory’s actions, and his attacks were often personal. On May 7, 1868, Kirk took offense to some of Mallory’s statements and challenged him to a duel at The Dueling Oaks. When the challenge was discovered, officers from the Pensacola Police Department arrested Mr. Kirk. As soon as Kirk was released, he challenged Mallory again at the same location. A constable was summoned and arrived just in time to stop the duel before the shooting began (Brackett, p51).

On March 4, 1881, the Pensacola and Atlantic Railroad was chartered, and on June 1 of the same year, construction began. The track ran through the middle of Dueling Oaks and across the 17th Avenue trestle, also known as Graffiti Bridge. Later, the southern half was made into Frascati Park and the northern half was eventually purchased by the Wilder family.

Okay, admit it. As primitive as it sounds, there is something about a duel that is really exciting and manly. Some say that boxing matches, wrestling matches and other sports have taken the place of duels. Uh…NO! What about golf? Video games? COME ON!!!

Police Duties

Privies: In the days before indoor plumbing, water was either drawn from a well or carried from one of the creeks located on each end of town. Of course, indoor bathrooms were not in existence. Privies (outhouses) were used. On July 17, 1824, the Pensacola Gazette published a city ordinance that was originally enacted on November 16, 1822 stating that all privies within the city limits of Pensacola be at least 3 feet deep. Those less than that depth by January 1, 1823 would be fined $5. If the owner of the privy continued to ignore the ordinance, the city would dig it out and charge the owner for the work. Whose job was it to measure the privy to ensure it met the three-foot minimum? The police.

Hogs & Goats: A city ordinance was passed on April 14, 1834, that required everyone within the city limits to keep their hogs & goats tied up. Any hogs or goats found loose would be rounded up…by the police. The police would then take the wandering hogs & goats to the police station and keep them while an ad was put in the local paper. The owner was to pay the fine and pick up the animal. If no one claimed it, the police would sell it, and the proceeds would go to the following: 50% to the city treasury and 50% to the police department.

Keep your kitchen clean: In the 1800s, the city commission determined that unclean kitchens were not safe. Therefore, they determined it to be the duty of the Pensacola City Marshal and his officers to inspect every kitchen and premises within the city limits to make sure that they were kept clean. Failure to clean your kitchen would carry a $5 fine.

Bathing Naked: Without modern bathing facilities and bathrooms, personal hygiene was maintained in a different manner than it is today. The most abundant supply of water came from Pensacola Bay. However, as the town became more inhabited, bathing in the bay was no longer an option. So the city commission addressed the problem. On May 6, 1837, it enacted a new ordinance, “No person is allowed to bathe naked during the day in front of the city between Town Point (approx. 9th and Bayfront) and Bayou de la Aguada (‘A’ and Main Streets).”

Can’ts: In 1837, the police were required to make sure citizens didn’t…

- Shoot guns without asking the mayor first

- Run a horse or mule on the street or the sidewalk in the city limits

- Maim their animal in public

- Leave their cart, dray or wagon in the street after dark

- Roll a barrel in the street or sidewalk in the city limits

- Fail to keep a 12 ft ladder in their yard

- Fail to have a well in their yard

- Have enough soot in their chimney to start a fire

- Water their horses in the public springs – the drinking supply for citizens

- Cut down the city’s trees or the Market House

- Ring the City Bell if they were not the police

- Own or operate a gambling facility

- Have a store or business open on Sunday

- Store or sell any fruits or liquors from their house

The Arrest of John Wesley Hardin

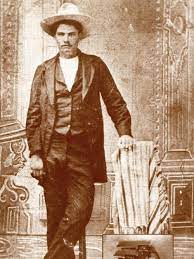

Rumor has it that he shot a man for snoring too loudly. “In self-defense” he claimed he killed 40 men. Research has shown that many of them were killed in cold blood. His name was John Wesley Hardin, and he was one of the most infamous and feared gunfighters in the history of the Old West. One of the men Hardin killed was Comanche County, Texas Deputy Charles Webb. An arrest warrant for Hardin was issued for murder. Hardin may have been deadly with a gun, but he was no match for the Texas Rangers, who would be hot on his trail. Maybe he and his gang could get away to Florida. It would be quieter, and his partner, Robert Joshua “Brown” Bowen had family there. Hardin and Bowen headed east. Bowen had his own troubles, being a robber and murderer in his own right – he had active warrants for murder and escape. Pensacola was 797 miles away. Sounded good.

Hardin and his gang settled in nearby north Santa Rosa county with the Neill Bowen family near a community that later became the town of Jay. “Life will be simpler now” he told himself. However, like many people, Hardin believed that the problem was the location. Not true. The problem was inside Hardin. Consequently, John continued in his habits. Under the alias “James W. Swain,” he began hanging around in Pensacola, occasionally gambling and getting into scraps with others, but always under the radar. Mr. Swain was even familiar with Sheriff Hutchinson and Marshal Comyns.

Unbeknownst to Hardin or Bowen, the Texas Rangers, on the trail of Brown Bowen, had put an undercover Ranger on the case. Hardin’s wife, Jane, was surveilled daily. They intercepted Bowen’s mail and kept track of every person he contacted. One letter they intercepted revealed that the gang – including Hardin and Bowen – were living in or near Pensacola. A road trip was suddenly planned by Texas Rangers John Armstrong and Jack Duncan.

When William Chipley, superintendent of the Pensacola & Atlantic Railroad (and later mayor of Pensacola and Florida State Senator) learned that the Hardin gang was to catch a train at the Pensacola L&N Freight Depot, he accompanied the Rangers, Sheriff Hutchinson and Marshal Comyns to the train. A posse of Pensacola Police Officers and Escambia County Sheriff’s Department Deputies were also on hand. Hutchinson, Duncan, Comyns and Chipley entered the train and apprehended Hardin before he could draw his weapon. However, one of his gang was fatally wounded in a shootout. Armstrong and Duncan escorted Hardin back to Texas where he stood trial. On June 5, 1878, John Wesley Hardin was sentenced to 25 years in state prison – finally ridding the world of the danger of this killer. He was released on February 17, 1894. On August 19, 1895, was shot in the back of the head by John Selman, Jr., killing him instantly.

The First Breathalyzer

There is a saying… “Advances in technology bring problems.” The automobile is one of the most significant breakthroughs in technology in history. However, with the introduction of automobiles came the need for red lights and traffic laws. Driving automobiles also introduces something else that is new – drunk drivers. In the past, there was never a need to determine if a person was driving drunk because there were no automobiles, so the infringement was not common or dangerous (except bicycles and boats). With the advent of cars came the need to determine the amount of “drunkenness.” The evolution of drunk-driver testing instruments went from the officer’s opinion to the drunkometer to the breathalyzer to the intoxilyzer (so far).

“Police Take Guesswork out of Testing Alcohol.” That was the title of a newspaper article written about the first Breathalyzer purchased in Pensacola. Sgt. D. P. Caldwell, the instructor, gave an interview about how accurate the instrument was compared to the old drunkometer, which had been in use since 1931. It was a new and innovative tool for police departments to use. The instrument ushered in a new era of keeping the roads safe by stopping people who were driving drunk.

In the early 2000s, the author was visiting with Retired Chief Caldwell. As we talked about his days as a police officer, he suddenly stopped and said “You have heard about the breathalyzer, haven’t you?” The author explained that he knew what it was, but that the breathalyzer was replaced years ago by the intoxilyzer, which is the instrument of choice in the 2000s when a person is suspected of impaired driving. Chief Caldwell replied:

Well, you know, we used to use a Drunk-O-Meter. Some people called it a “Dial-a-drunk” because it was easy to manipulate. It was inaccurate, so something had to be developed to take its place. When I was the department’s administrative sergeant, I had heard about a new instrument called a Breathalyzer, and I thought it would be good if my department could get one. I contacted the inventor, a member of the Indiana State Police, and asked him if he could come to Pensacola to demonstrate it for us because we were interested in purchasing one. He agreed. The officer – I can’t remember his name – arrived on the appointed evening at the San Carlos (Hotel) where the Pensacola PD had put him up. Needless to say, there was a lot of excitement. Visitors, dignitaries, media representatives, and police administrators were going to be there the next day. As soon as the officer arrived with the breathalyzer, he pulled me aside. ‘I need your help!’ he told me. ‘This thing is brand new. I just built it and I know it works, but I have never tried it out! We need to try it out before the official demonstration tomorrow!”

Sergeant Caldwell, being a teetotaler, immediately found a willing volunteer to begin downing some drinks to test the new instrument. So, in a room in the San Carlos Hotel at Palafox and Garden Streets, the very first Breathalyzer test in history was performed. And it performed wonderfully. The demonstration went off the next day without a hitch – according to Drexel P. Caldwell.

As it turns out, the January 20, 1958 edition of the Pensacola News Journal ran an article about the drunkometer that paralleled what Chief Caldwell stated. It stated: “The drunkometer, which was perfected by Capt. Robert F. Borkenstein, director of the Indiana State Police Laboratory, is a semi-automatic colorimeter with photoelectric cells.” Of course, the instrument was named incorrectly and the technical description probably impressed some and confused others, but the article documented the test that paved the way for a more accurate instrument used in law enforcement!

The Dark Side

One of the saddest periods in the history of the Pensacola Police Department occurred during Chief Crosby Hall’s tenure. The headlines of the December 8, 1960 edition of the Pensacola Journal read: “Owner’s Records List 45 Cops in Pay Charges.” Mrs. Lois Sheffield was the new owner of Sheffield’s Garage. She took over the business after her husband, longtime owner Bill Sheffield died.

According to Mrs. Sheffield (and later corroborated by many officers), police officers received payoffs from Mr. Sheffield for bringing business his way. It worked like this: When a vehicle accident occurred within the city limits, it was (and still is) investigated by the Pensacola Police Department. Unless a driver requested another wrecker service, most officers either recommended Sheffield’s or simply called on the radio for them to respond. A small percentage of the fee would be paid to the officer. Of course, this is illegal, and Mrs. Sheffield hated the practice, although her husband ran it, and it brought in a lot of money for her family.

After the death of her husband, Lois Sheffield stopped the practice of these payments to officers. Of course, officers – many of whom didn’t know the action was illegal – were unhappy, and they let Lois know about it. There was talk that threats were made to her. Because the practice was continued and payments demanded by officers, Lois went to the Pensacola Police Department superiors. But the administration did nothing. Frustrated, Lois brought records to the local AAA motor club and to the media. The records showed payoffs listed to officers from February 1959 – April 1960, when her husband died. After that, she said she was pressured from officers to resume the $10 payoffs for business sent her way during crash investigations. As it turned out, 17 were charged, two were acquitted, and 15 cases were dropped.

Then, while the Department was still trying to recover after the wrecker scandal, things got worse. In April 1961, eight Pensacola police officers and two Escambia County Deputies were arrested as being part of a burglary ring. An explanation to the author of how the process worked is this: an officer would approach a business, break out a window, take a television, put it in the trunk of his car and call in a burglary. Another common practice occurred when an officer, at the scene of a legitimate burglary, was offered property by the business owner, who would then include it in the stolen items list. Of the PPD officers, three served time in prison, one received probation (off the force), and three were acquitted. The eighth, John Trevathan disappeared and was never heard from again.

Most officers and other PPD employees that were working at the time of the scandals all agree that many other officers were involved in both of these events but were never caught or charged.

Pensacola’s Connection to the JFK Murder

We have all heard the story: President John F. Kennedy, our 35th, was sitting in the rear of a convertible, touring downtown Dallas on November 22, 1963. As he turned onto Dealey Plaza, Lee Harvey Oswald pointed a rifle at him from the Texas schoolbook depository and fired the shots that ended his life. Then, after Oswald was charged, he was killed by Jack Ruby, the local night-club owner who was such a patriot that he shot Oswald out of hate. The end. Period. Maybe…

Follow-up investigations rubber stamped the original reports. But then came the questions. Questions about Cuba’s involvement, the FBI, the vice president, the CIA and the military. What about the questions regarding the local police, the mob, Cuban exiles, New Orleans, and the combinations presented by those possibilities listed? Documentaries and scientific recreations conclude that the murder could not have occurred the way it was originally supported. Could the assassination have been a plot born from a conspiracy? Yes, hundreds of them. Further, there were the fringe reports. One guy knew someone that knew someone that was related to Oswald, and now he is dead. The Warren commission, a panel brought together to investigate what happened, concluded that it was a straight-forward, no-nonsense, Oswald murder.

Then came technology. When re-creations and sound bites and eyewitness testimony are put together, the result could not have been Oswald alone. Finally, the television shows came out. The movie “JFK” led the crowd. Whatever they did, they caused people to reconsider what might have happened. Many theories still abound, and many have very plausible possibilities.

Hank Killam, a Pensacola boy, often found himself in trouble growing up – in school, the neighborhood and in his family. As a teenager, his troubles increased and often involved the police. Thefts, burglaries, fights, etc. are examples of his regular trips to the police station. Hank was big – he stood over 6 feet tall and weighed over 200 lbs. He was also a good-looking kid, but he had trouble abiding by the law. When he was put on probation, he couldn’t follow the rules, so he absconded. He landed in Dallas, Texas, where he lived for about five years. He met and married Wanda Davis. Wanda was a cigarette girl, dancer, and stripper in a club – a club owned by Jack Ruby. For a while, Hank even worked as a bouncer for Jack. For work, Hank also sought out and befriended John Carter, a house painter. John hired Hank to work for him. John lived in the same boarding house that Lee Harvey Oswald lived in. As a matter of fact, John also knew Wanda, and the three of them (Wanda, John, and Hank) often talked together, maybe about things they shouldn’t be talking about, at Jack Ruby’s club, the Carousel Lounge.

On the day of the president’s assassination and the capture of Oswald – November 22, 1963 – Hank came home from work, pale and shocked, Wanda recalled. She figured he was stunned that his president had been assassinated in his town. Of course he was shocked. Everyone was shocked. But…was it more? Wanda said that Hank stayed glued to the television that night, watching the latest reports. He became more and more agitated and paranoid. Investigators from different departments – both local and federal – sought him out constantly. He complained that “plotters” wanted to speak with him and kept harassing him. Wanda was certain he was afraid of something. Suddenly, a few months after the assassination of the president, Hank informed Wanda that he had to leave. He had to get out of Dallas. He moved 1138 miles away – to Tampa, Florida. He began selling cars there. However, he made the mistake of talking too much about his destination, and “agents and plotters” (as Hank referred to them) soon drew the information from Wanda. They found him in his new job and began “hounding” him again. From place to place he went, trying without success to keep a job in one spot, becoming more mistrustful of everyone. In March 1964, he couldn’t stand living in Tampa any longer. Even though he felt certain that a warrant existed for his arrest, he made the decision. He left for his childhood town – Pensacola.

On March 15, 1964, Hank arrived in Pensacola. He went to the home of his mother, Mary Killam, at 316 W. Romana Street. As they were talking, he told her that he was frightened about what might happen to him. Soon he made contact with his old friends and got caught up about old times. While speaking with his brother Earl about the JFK situation, he said “I’m a dead man, but I’ve run as far as I’m going to run.” He let Earl know that his concerns stemmed from not being able to escape the long fingers associated with the JFK ordeal. Hank stayed with his mother – for two days.

On March 17, Hank got a letter in the mail. He read it, and a deathly fear came over his face. He kept mentioning that he was afraid, but his mother didn’t know what he meant, nor did she want to. That evening, his paranoia rose to the point that he began talking to himself and walking around in the house and yard. At 1:35 on the morning of the 17th, Mary, desperate for some help, called the police. Pensacola Police Officer Henry Reeves responded, along with others. One of the other officers remarked “It’s just Hank. Don’t worry about it.” Hank had worked as an informant for the PPD before, so they apparently didn’t think he would be in danger. Mary told Officer Reeves that Hank had had mental problems and that he had been having black-out spells recently. She had an appointment later in the day for him to see a psychiatrist. Reeves tried to get Mrs. Killam to take Hank to the emergency room, but she resisted, promising to take him to the doctor later that day. Officer Reeves, knowing Hank, then talked him into going to bed and getting some sleep. Hank obeyed. Officer Reeves instructed Mary to sit outside his door and make sure he didn’t leave. She agreed and Reeves left.

Around 3 am, Hank and Mary were awakened by the ring of a telephone. Hank talked for a few seconds and hung up. Mary went back to sleep in the chair outside her son’s room. A few minutes later she woke up when she heard a car door slam and a vehicle drive away. She thought it was strange, because the Killams didn’t own a car. Suddenly, a strange, cold feeling came over Mary. It got worse when she discovered that Hank was gone! At 3:40, she called the police again, worried because Hank had not returned. Officer Reeves again responded. As Reeves was searching for Hank, he got a call about a body lying in a pool of blood on the sidewalk on the Northwest corner of Palafox and Intendencia – just four blocks from the Killam home.

The view that Henry Reeves found when he arrived was gruesome. The huge plate-glass window of The Linen Store, 125 S. Palafox Street was shattered, and glass was lying everywhere. Inside the store were bloody footprints, marking as far back as six feet from the broken window. But all of that paled in comparison to what was in the middle of the sidewalk, 35 feet from the window. There lay Hank Killam in a pool of his own blood with his throat cut. Reeves called for an ambulance and Hank was taken to Escambia General Hospital where he was pronounced dead. At first, the police ruled the death a suicide, while the coroner’s office ruled it an accident. When they were questioned, one officer said that they were told to “shut it down” and not talk about it anymore. No autopsy was ordered or conducted.

On February 22, 2019, the author interviewed Elton Killam. For many years, Elton practiced law in Pensacola. He is also a cousin to Hank Killam. Not satisfied with the shallow investigation that the Pensacola Police Department conducted, he made numerous contacts, conducted interviews, read books, and watched movies in an attempt to find the truth. He explained the situation to the author of the death of his cousin.

The Warren Commission, the JFK movie, other investigations, movies, television shows, books and articles have been written since JFK’s assassinations. Many people have said that they have finally found the answer…but no answer has been found yet. Also, rumors abound about the number of witnesses to the JFK assassination who had a similar end to Hank Killam. The numbers range from 15 to 100+. No one knows – or has ever proven – that there are any connected deaths, but it appears that the death of Hank Killam might have been one.

Murder for Hire

For 17 years, they worked together. They were friends – close, as cops often are. That’s why Sgt. Lucien Mitchell was surprised when his buddy, Sgt. Isaac Halford came to him one day at police headquarters and offered him money to “take care of someone.” Mitchell asked Halford what he meant by “take care of someone,” to which Halford replied “by killing them.” Mitchell was no stranger to tough situations. After all, he had been a cop for a long time. In addition, Lucien had that kind of reputation. Many people commented “Wow! I would have come to him also.

If anyone could kill someone, Lucien could!” After all, he had been in some scrapes before. Lucien put a notch on his gun handle every time he killed a man. So far, there were six, but they were all legal. But to murder an innocent lady in cold blood – he didn’t want anything to do with that. Lucien didn’t answer right away. He knew he would have not part in a murder, but he contemplated what to do.

Jim Naes and Gerry Naes lived what appeared to be very comfortable and successful lives. They had three children, lived in an upper-middle-class neighborhood and both drove nice cars. Jim had a good business that provided the family with the means to live a somewhat extravagant lifestyle, which often landed them on the society page of the local news. Not all is as it seems, though. The home was not a happy one. On December 3, 1973, they divorced. The judge’s decision left Gerry with custody of the children, the house, child support, alimony and a lump sum of $20,000. This did not sit well with Jim at all. After all, he was used to getting his way. He had worked hard his whole life and now he should be reaping the benefits of that hard work. He checked with his lawyer – he wasn’t able to change the judge’s mind or to “overrule” his decision. There was, however, something that he could do. He contacted his friend, Pensacola Police Sergeant Isaac Halford, and offered to pay him $5000 to murder Gerry. Maybe Halford was not up to the task or maybe he felt he was too close to the situation, but he in turn contacted Sergeant Mitchell and made the offer to him.

Lucien listened, shocked and amused inside. He didn’t say anything at first. All he knew to do was to report the offer to State Attorney Curtis Golden, which he did. Everything that Lucien did after that was part of an investigation under the supervision of Golden. First, while being recorded, he contacted Halford and got the contact information. The recorded telephone phone call was made to Naes, who agreed to meet Lucien at #212, Wellington Arms apartments. Lucien showed up in plain clothes, wearing a wife. Jim Naes gave Lucien $2500 and promised him another $2500 upon completion of the task. After the transaction, on April 30, 1975, Lucien met with Halford and gave him $500 in marked bills as bonus money for setting the job up. Halford pocketed the money. Everything was recorded. A few minutes after the meeting, Halford, who had gone to the Escambia County courthouse on other business, was approached by two of his fellow officers – Perry Knowles and Mike Thompson. To his surprise, they placed him under arrest for conspiracy to commit murder. Meanwhile, Jim Naes left town on a business trip to Alabama.

When a person is arrested on a warrant from another state, he is taken to the nearest jail and held there until a hearing can be arranged to see a judge – usually the next day. If the person refuses to waive extradition to the state that wants him, he must remain in jail until a Governor’s Warrant is applied for. The extradition can take three months! So, when Jim Naes was contacted and informed that a warrant existed for his arrest for conspiracy to commit murder, he agreed to return to Pensacola in his own vehicle and turn himself in, which he did. Both men eventually made bond – Jim for $50,000 and Halford for $10,000.

While Jim was out on bond, the Pensacola Police Department provided round-the-clock security for Gerry and the kids, even though the residence was out of their jurisdiction, in Escambia County.

With protection from harm, and with the realization that the case was set for trial, Gerry Naes was safe. From all indications, she would be able to live and to raise her children in the same relative manner that they were all used to…except for one thing. With Jim in prison, there would be no financial support from him. He would not be able to pay child support or alimony. Gerry would suddenly be taxed with raising three children and providing income for the household. It was overwhelming. However, instead of a lengthy prison sentence, if Jim were sentenced to probation, he could continue working and help with the finances. So, Gerry found herself arguing for leniency for the husband who betrayed her and paid to have her killed. As soon as the case was settled, Jim fled to St. Louis and remained there. Gerry never saw any support. Life is full of irony.

The Deadly Train Derailment

People from across the world talk about the breathtaking view of the sugar-white beaches on Santa Rosa Island. Indeed, it is unique and beautiful. Not only is the sand pure white, but the water is a crystal-clear emerald color. A little-known fact about the shore along West Florida: People living on the East Coast of the United States love to watch the sunrise over the Atlantic Ocean, and people who live on the West Coast love to watch the sunset over the Pacific. People who live on the Gulf Coast can see the sunrise and the sunset over the Gulf of Mexico every day!

Locals, however, love the view of Escambia Bay afforded them by looking out from the bluffs on the East side of town. Scenic Highway, which meanders along the bluffs, offers an elevated view of the bay, the David Bogan Bridge, Garcon Point, Gulf Breeze and the CSX railroad tracks along the water’s edge. At night, the calm and serenity the view offers are second to none.

Such was the case early on the evening of Wednesday, November 9, 1977. However, that would change in a moment. The Thorshov family was finally relaxing after a long day’s work. Dr. Jon Thorshov, his wife Lloyda and the girls – Daisy and Gamgee – were enjoying the mild Pensacola November weather when they suddenly heard a loud crash. It was the dreaded, unmistaken crash of a train derailment. It was normal for trains to come along the tracks near the Thorshov home. They passed by several times a day…so much that the family usually didn’t even notice. So, there was not out of the ordinary when two SD-45 locomotives pulling 35 cars moved along the tracks near the Thorshov home. What was out of the ordinary was the crash. The Thorshovs lived in an area called Gull Point, east of the intersection of Scenic Highway and Creighton Road. Without warning, the train suddenly derailed, spilling its cargo all along the bluffs. Some of the cargo was anhydrous ammonia, a toxic chemical which produces a deadly vapor that permeated the entire Gull Point area. At 6:09 PM, 35 cars ran off the tracks about 40 yards from the Thorshov home. Dr. Thorshov, a local pathologist, and his family were rushed to the hospital and treated for exposure to the deadly fumes. According to the Centers for Disease Control website, anhydrous ammonia is a colorless gas or liquid with a pungent, suffocating odor whose symptoms cause irritation to the eyes, nose and throat. It causes breathing difficulty, wheezing, chest pain, pulmonary edema, pink frothy sputum; skin burns, vesiculation and liquid frostbite. Dr. Thorshov died that night at the hospital of suffocation from his injuries.

Without advanced warning, Pensacola Police Officers found themselves undertaking the overwhelming task of evacuating 600 area residents from Interstate10 to Langley Avenue, and from Spanish Trail to Escambia Bay – about 2 square miles, while battling a deadly fog. Meanwhile, 500 residents from south Santa Rosa County were evacuated, due to the fact that the toxic cloud of anhydrous ammonia gas floated east over the bay and toward the Garcon Point area. While many people commented on the dangers that the residents were exposed to, most people didn’t consider that the officers voluntarily went into the toxic area to rescue others.

The first indication came from an emergency phone call to Dispatcher Jerry Potts. A resident in the area heard a loud crashing sound and he knew, without even looking at it, that he heard a train derailment. Other calls were made reporting a cloud over the highway. Officers were immediately dispatched to respond and investigate.

Officer Scott Pelham, the first officer on the scene, was working Patrol in that area. Scott described a frightening scene. He was the officer who received the first call about an explosion. Not knowing what the situation was, he responded with his lights and siren. As soon as he arrived, the crash was obvious, as was the danger of being in the area. He backed out, turned around and left the area, checking on homeowners as he left. As it turned out, that decision probably saved his life, or at least a hospital stay. Less than a mile down the road from where he stopped a deadly toxic cloud hovered over the road.

The derailment came close to home for Investigator Wes Cummings. Driving home from work, Wes passed through the intersection of Creighton and Scenic that became deadly 10 minutes later. He heard a call on the radio of possible smoke at the intersection he had just passed through. Before the night was over, his next-door neighbor was exposed and had to be taken to the hospital.

Officer Bill Chavers was also working that night. When dispatched, he responded. “I almost drove into the clouded area. Later I was assigned the task of driving out to the little point area at the end of Creighton to check the small group of homes. It was like the movie Andromeda (warring against uncivilized chaos). The fire department provided an air pack for me to use. The homes were abandoned, doors open, food on tables, TVs on, everything laying out because the people had immediately left the area. It was scary and weird.”

Rookie Officer Greg Moody responded to the explosion as well. Without much training or experience, he thought it probably wasn’t a good idea to drive through the huge white fog that hung over the highway. He turned around. Good move. He spent the rest of the time assisting residents out of the area and helping other officers with traffic direction.

Pensacola Police Officer Lamar Pate recalled that night well. He was patrolling the west side of town with Officer Sammy Mayo – two to a car. Since all available officers were needed at the site of the derailment on the east side, Officers Mayo and Pate had to handle all calls on over ½ the city of Pensacola – one police car and two officers to cover half of Pensacola.

Within minutes the disaster was widespread. Some officers were called in to work, and the relaxing night they were expecting never happened. The initial phone calls to the police department were followed by thousands from across the globe. Worried residents called to see if the cloud would float in their direction, members of the media wanted more information, and out-of-town friends and relatives called to find out about loved ones who might have been affected. The dispatchers and desk sergeant had to have additional officer assigned to them to handle the overwhelming radio and telephone traffic.

Emergency shelters were set up at Bayview Community Center and two local churches. Three shelters were set up in Santa Rosa county. At least 18 people were taken to area hospitals. While the highest number of victims was taken to West Florida Hospital, Sacred Heart took in the most severe, the Thorshov family. Besides the death of Dr. Thorshov, his wife and two children were admitted, listed as critical the first night.

In the aftermath, city and county leaders were angry over the seemingly lack of concern that L&N officials had for the disaster. According to the Pensacola News Journal, 20 derailments had occurred in West Florida in the past 30 months, many of them containing toxic materials. Discussions took place to ban all toxic chemicals into Pensacola. While many councilmen and commissioners talked with the media, Commissioners Kenneth Kelson and Marvin Beck were at the scene as quickly as they could get there.

A consequence that emerged as a result of the evacuations was that of looting. In the evacuated areas, residents were prevented from going home anywhere from 24 hours to several days, according to where the homes were located and how close to the scene they were. Officer Mike Maney recalled that he and several other officers were assigned to patrol the off-limits areas for a few days for unauthorized persons.

Officer Skip Bollens was there. He tells this story: “I had finished work for the day and was called back to work traffic control at Scenic and Langley. A newsman kept insisting he had to go North on scenic (toward the crash scene). He refused to turn around or go South. I finally indicated East (dead end toward the bay, not the crash) and he took off 10-18 (in a hurry). As he arrived in full speed at the dead end, he slammed on his brakes. I thought he was going to slide all the way to the railroad tracks that made their way past the dead end! He finally left, telling me what he thought of me. I was relieved in time to go to Red Cross van for coffee and a hot dog before heading back to work for the next day. I was at the Incident Command when the national news cornered Sgt. Powell for a news release. Cameras rolling, live feed, they asked what had happened. The salty sergeant stated in a slow, southern drawl “The train fell off the track.” Irritated, they stopped and backed off until releases were made.

Just as Pensacola felt it could breathe again, a related tragedy struck on Sunday, January 22, 1978. 74 days following the disaster, Mrs. Lloyda Thorshov succumbed to the injuries she suffered from the derailment, leaving her two children without either parent. The official cause was listed as respiratory failure. A lawsuit brought against L & N brought sweeping changes, not only to the tracks along Pensacola’s scenic bluffs, but also to the entire railroad industry. Much needed improvements and safety measures were implemented, making rail travel safer.

As sad as the event was, had it not been for the courageous acts of the officers of the Pensacola Police Department, the firefighters of the Pensacola Fire Department, neighbors and citizens, the death toll would have been much higher.

The Capture of Ted Bundy

Working the graveyard shift is…different. Sometimes it’s slow, sometimes it’s crazy, and sometimes it’s – creepy. When the world is winding down, midnight shift workers are just beginning. Some police officers like it while others hate it. There are a few advantages to working the midnight shift. The streets are usually less busy, the officers are usually less busy, and the heavy brass of the department is not at work, making for less tension. However, a common statement by officers is “If you get into something on midnights, it’s really big!”

1:30 AM on Wednesday, February 15, 1978 was a quiet time for David Lee. Officer Lee was a Pensacola Police Officer, working the midnight shift on the west side of Pensacola. Two of the qualities of a good beat officer are to know the people and businesses on his beat and to protect them like a guard dog. That is what Officer Lee did. As he usually did when working midnights, Officer Lee was checking the buildings on his beat. His main objective was to prevent and foil burglaries.

Old friends met there. It was that kind of place – when you walked in, you probably knew somebody, or felt like you did. Most people loved eating at Oscar’s Restaurant. When it was open, the parking lot was usually full. And it was not unusual to find one of Pensacola’s Finest eating there. It was a Pensacola icon. Located in an old building in a less-than-affluent area of town, Oscar’s had that special charm that drew people to it. It felt…familiar.

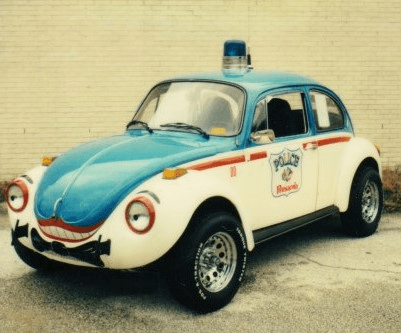

David Lee drove his patrol car slowly through back streets, between the businesses and along Cervantes Street. He used his spotlight to better see that neighborhoods and businesses were safe. As he eased his cruiser behind Oscar’s Restaurant, 2805 West Cervantes Street, he saw an orange Volkswagen Beetle slowly making its way through the parking lot. This sight attracted David’s attention. Like all good beat cops, he knew the employees at Oscars and what they drove. “Strange” he thought to himself. “Nobody that works here drives a VW. He tried to think of scenarios that would cause such a sight. He considered driving off, but the guard dog in him convinced him to go back, so he decided to check it out. Just then, the vehicle fled from the parking lot. As Officer Lee followed it, he called in his situation on the radio, checking the tag. It came back as a stolen vehicle belonging to Kenneth Misner from Tallahassee. This transmission attracted the attention of other officers, who headed toward David.

Officer Lee prepared to stop it and possibly find out why Mr. Misner was cruising in his town behind Oscar’s Restaurant. However, the Volkswagen sped up in an obvious attempt to elude David. Finally, he stopped the Volkswagen a mile and a half up the road. He pulled it over outside the city limits at “W” and Cross streets near Catholic High School. David didn’t know what he had. He did know that he was approaching the driver of a car parked behind a closed business (in HIS area of town), and that the vehicle fled when he approached it. Not taking any chances, he ordered the driver out of the car and made him lie down. When Lee approached, the man kicked Lee’s legs from under him and a fight ensued. Finally, the man broke free and began running northeast into the neighborhood. Lee chased the man through the area, finally firing two shots. As he approached the man, Lee was attacked and another fight began, but this time over the gun. Lee and responding officers finally subdued the man and placed him in cuffs. He was taken to jail. A search of the man’s possessions and of the contents of the car revealed several documents, including many credit cards, in the name of Kenneth Misner, the owner of the stolen car. Things didn’t add up. Why would a man be driving his own stolen car?

Detective Norman Chapman lived 40 miles from the police station, near the small town of Jay, Florida. He lived out in the country, and his accent and mannerisms reflected his laid-back country life. When Norman got out of the U. S. Army, he decided to become a Pensacola Police Officer. Soon, he was transferred to Investigations as a detective. In the early morning hours of February 15, Norman’s phone rang.

“Sorry to wake you detective, but you need to come in. Officer Lee stopped a vehicle that is listed as stolen out of Tallahassee. We have the driver in custody.”

Rubbing the sleep from his eyes, Norman began the business of getting dressed and heading out. Detectives make a habit of having clothing and equipment laid out – just in case they are called into work during the night. When Detective Chapman arrived, he met the man…who agreed that he was Kenneth Misner. The man was not used to Norman’s slow, southern drawl, but he liked him. The man made the mistake of believing the stereotype of a southern country boy being slow and backward. Chapman interviewed the man and immediately made a connection with him. Chapman sensed there was something different about this man who called himself Kenneth Misner, something unusual that the man was hiding. Chapman established, not a friendship, but a relationship with the man which would last for many years. The man was very personable and extremely intelligent. However, he was proud of himself. His pride was the element that Detective Chapman focused on. In an almost Gomer Pyle manner, Norman acted as if he was fascinated with the man’s intelligence. As he freely spoke with the man, something wasn’t right. He had just been arrested in a stolen car with stolen items, fled from the police, then tried to take an officer’s weapon. Yet he appeared relaxed and smooth. He was personable – almost charming. How would a man of his intelligence and ability find himself in this situation. It didn’t feel right. The man was fingerprinted and his prints immediately sent to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. After a period of time, the FBI identified the man through his fingerprints. His name was Theodore Robert Bundy.

Ted Bundy’s name had been in the papers and on television across the United States. He was last seen in the northwest, where he escaped and fled. He was on the FBI’s Ten Most-Wanted List. The infamous serial murderer and escape artist had disappeared from the Glenwood Springs, CO Jail and resurfaced in Pensacola. During the hours that Chapman interviewed Bundy, he made statements that were to prove significant in the murder case of Kimberly Leach, a 12-year-old girl who was murdered in Lake City and buried in a shallow grave nearby. Bundy was subsequently found guilty of this crime and sentenced to die in the electric chair.

The information that Bundy related to Detective Chapman was important to the case. As Bundy’s date with electric chair “Old Sparky” neared, he requested that Chapman, now the chief of police, come to visit him on death row. Chief Chapman knew that Bundy wanted to tell where more bodies were buried. It was obvious that Bundy wanted to extend his life by having additional charges brought against him, therefore postponing his execution. Chapman refused to see Bundy, who was put to death on January 24, 1989.

National Airlines Crash into Escambia Bay

“They have lost an airliner from the radar…It just disappeared…This is not good.” Pensacola Police Officer Jim Simmons was talking to his family at home. Jim, the author’s father, was one of the police officers assigned to the Pensacola Regional Airport. He had been at work at the airport that day, May 8, 1978, and had only been home a few hours. Just after 9 pm that night, he received a phone call from the airport dispatcher, informing him that the FAA officials in the tower had lost track of a National Airlines 727 jetliner they were monitoring. The airliner had lined up to approach the runway from the east, right over Escambia Bay and Scenic Highway. As it came close to the bay, it disappeared from the radar.

The weather was bad that night. As a matter of fact, the FAA officials had just diverted an Eastern Airlines plane to Mobile because of the weather. The next plane to approach was National Airlines Flight 193, and it dropped from radar as it was approaching. Jim explained that the disappearance of the plane most often means the plane dropped below the altitude that can be picked up on the radar. He said that it was possible that the plane simply dropped too low over the water, but that was not likely – all indications were that it had crashed. As he said, it was not good. He decided to get dressed and return to the airport. It looked like it was going to be a long night.

Almost immediately, the phone calls started coming into the police emergency line about an airplane in Escambia Bay. The jet, a Boeing 727, had 58 reported souls onboard. At that time, National Airlines had a policy that every airplane had a nam,e which was written on the side of the aircraft. This one was named Donna. Officer Scott Pelham was the first officer on the scene. Six months earlier, he had been the first officer on the scene of the L & N derailment. Of course, after his arrival and his initial reports about what little he had discovered, keeping a lookout for debris, survivors, etc. was all he could do. He felt helpless.

A huge advantage to landing in the bay is, of course, it makes for a soft landing. This is why no one died during the crash landing. However, the problems that come with a crash at night in the middle of a body of water are many. No one – passengers, families, airport officials, or crewmembers – even really knew where the plane landed. They did not know if it was in one piece or thousands. Rescue was difficult – it took boats to get people out. It was dark, so people couldn’t even see the plane. Not a good situation.

At the Pensacola Regional Airport, loved ones who were there to greet the passengers waited for word on the plane. At first, they thought it might be late. But then they could tell that there was a problem. Between the airline employees, airport officials and police scurrying about in an unusual manner, they soon sensed something bad had happened. Eventually, they were told that it appeared the plane had crashed. Reactions ranged from calm to weepy to hysterical.

As is often the case in emergencies, the best and the worst come out in people. The jet had crashed into Escambia Bay in 9-12 ft of water close to Garcon Point in Santa Rosa county. A barge that happened to be nearby approached the airliner, tied up to it, and began rescuing passengers. Fishing boats, pleasure craft, and law enforcement boats all came to the rescue. However, one nearby crab fisherman continued to check his crab traps, seemingly unaffected by the tragedy.

Scenic Highway, which overlooks the bay at the point adjacent to the crash scene, quickly became full of spectators. On each side of the road, cars pulled off and people got out and gathered to get a glimpse. The crowd grew to a point that traffic became yet another problem. All Pensacola Police traffic officers were called out and responded on motorcycles – not for the crash, but because of rubberneckers’ vehicles blocking traffic. Officer Rick Buddin recalls that he was called by his supervisor and ordered to get into uniform and report for work – immediately. The job of handling traffic was as hectic as the rescue efforts.

When the plane first crashed, the interior lights blinked and went out. Salt water mixed with jet fuel began pouring in the passenger cabin, causing panic. The flight attendants kept people as calm as possible, but that task was a difficult one. Most people immediately became willing to help each other escape. A two-year old boy was crying but was passed from one passenger to another until he was out of danger, on a wing under the care of a male passenger. Sadly, his mother wasn’t aware of his rescue, and drowned trying to locate him. Amazingly, out of 58 passengers and crew members, only three died, of drowning. Many people had injuries from exposure, burns, bruises, internal injuries, ingestion of jet fuel, and shock, but 55 of 58 recovered.

As with any disaster situation, there was some confusion. The command post was not set up at Garcon Point, the closest land to the scene. It was set up at the east end of the Escambia Bay Bridge, which was closer to hospitals and emergency equipment. However, as some of the passengers were rescued, they were taken to the nearest land and dropped off, leaving them unaccounted for by the officials. As a result, first responders were sent to both sides of the bay – Escambia and Santa Rosa counties. Officer Mike Maney was off duty at home when he heard about the crash. He proceeded to the command post to offer assistance. He and Officer Clayton Ard walked the beach on the Santa Rosa side searching for survivors, debris, etc., for several hours, but found nothing. At the time, the condition of the plane and the passengers was unknown. Detective Wes Cummings was working on a stakeout when he heard of the disaster on the police radio. He drove to the closest intersection to the crash. After meeting with Chief of Police James Davis, he conducted a foot recon along the shore on the West side of the bay for survivors or pieces of the airplane, but to no avail.

It was unclear for a long time how the crash actually happened. The airport’s largest runway, Runway 16-34 (later renamed 17-25), is also the one with instrument landing equipment. It had been out of operation for several months, so the smaller one, Runway 7-25 (later renamed 8-26), was being used. 7-25 did not have instrument capabilities, so a visual landing is necessary. The requirements for landing on that runway are at least one-mile visibility and a minimum 480 ft. cloud ceiling. On the evening in question, the visibility was four miles and the ceiling was 400 ft, making it a judgement call for the pilot.

On June 29, Pilot George Kunz testified before investigators with the National Transportation Safety Board. Kunz testified that as he was reading 1300-1400 feet on his altimeter while the actual reading was 300-400 feet. So, as he began his descent, he actually made contact with the water. Although the crash killed no one, three people drown in the bay as a result of the crash. Kunz, the co-pilot and the navigator were all fired from National Airlines, who began working to settle the many lawsuits that came from the incident.

The Black Widow

“He’s a lucky man…God’s been with him.” Those were the words of Albert Gentry, brother of John Gentry. Albert was referring to John’s two close calls with death. When John was serving in the military in the Vietnam War, he stepped on a mine while on patrol. The mine exploded under him causing severe injuries and a lengthy hospital stay, but no permanent injury. Then, on Wednesday night, June 25, 1983, John’s car exploded when he turned on the ignition in downtown Pensacola.

John Gentry was a wallpaper businessman from Pensacola. In 1983, John met a woman named Judi Buenoano, a nurse who lived in the nearby town of Gulf Breeze. Despite her nursing qualifications, Judi owned and operated a nail sculpturing salon. She appeared to be a successful businesswoman fromher lifestyle.

Ted Chamberlain was born on July 21, 1945 in the historic town of Attleboro, Mass. Both his grandfather and his father had been police officers, so Ted was destined to follow in their footsteps. Right out of high school, Ted joined the U. S. Army and was sent straight to Vietnam to fight in the war. After he got out of the Army, he returned to Massachusetts and joined the “family business” of law enforcement, becoming an officer in his hometown. In 1976, Ted became a Pensacola Police Officer. Ted retired in 2013, ending his 37-year career. During that time, he served in patrol, the Tactical unit (his favorite) and Investigations. Ted was the kind of officer who very much liked working with the guys. An amateur race-car driver, he always drove with the windows down and one foot on the gas & the other on the brake.

After the explosion, it didn’t take long to figure it was caused by a criminal act. Someone had deliberately set a bomb in the car. In the middle of the night, the phones of Detectives Rick Steele and Ted Chamberlain rang. In a 2019 interview with Ted, he said that he first suspected Judi when he arrived at the scene. Ted recalled “Instead of parking near the restaurant, she parked her corvette a long way off – why? After the initial incident, Ted interviewed Judi a few days later. Her arrogance bothered him. “She bragged that she earned $500,000 per year.” He later found out that the life insurance Judi took out on Gentry was for $500,000. One of the first crucial thing a detective does when assigned a case is to check the background of all the players. In the Police Department’s Records section, he searched for Judias Buenoano. Nothing. Ted had a sudden thought. A young Hispanic woman worked in the Records section, so Ted asked her “What does the name Buenoano mean in English?” “It means Goodyear” she answered. Bingo! He was introduced to several death investigations that had been worked involving husbands, boyfriends and…her son. The locations ranged from Pensacola to Colorado, and insurance money was involved in every one of them.

Detectives Rick Steele and Ted Chamberlain worked the case. As the case was looked into, Gentry’s fiancée, Judi Buenoano, was developed as a primary suspect. Further investigation revealed that Buenoano had previously tried to kill Gentry by using poison. In an attempt to improve his health, she began giving him a regiment of “Vitamin C” that would make feel better and be healthier, she told him. A task force involving investigators from all interested agencies was formed. Soon, the task force members began suspecting Buenoano in the death of her son, her husband, her common-law husband, and perhaps one or two more people. Each person had a life insurance policy paid to Judi Buenoano.

After a long and exhausting trial, Buenoano was, on March 31, 1984, convicted of pre-meditated first-degree murder in the death of her son, who drowned while on a canoe trip with Judy in the East River. She was given a life sentence. She was also convicted of the attempted murder of John Gentry and received a 12-year prison sentence for it. Because of the work of Steele, Chamberlain, members of the task force, and especially of State Attorney Russ Edgar, Buenoano was convicted of premeditated first degree murder in the death of her husband, James Goodyear, in Orlando in 1971. She received the death penalty and met her fate on Monday, March 30, 1998.

Pensacola Police’s Talking Car

“That’s it! Just like Herbie!” Pensacola Police Officer Mack Cramer was sitting in a crime prevention seminar in Tampa, and he heard about a “theme car” idea. It came to him – he could acquire a theme car for the Pensacola Police. And…it could have eyes and eyelashes and would talk and make noises – remotely. And it would be painted like the other police cars, but it could talk to the kids!